Lineages : Yoga and Advaita

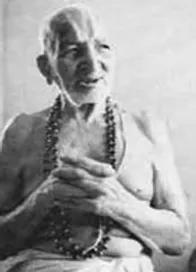

Sri Trimulai Krishnamacharya

Professor Shri T. Krishnamacharya (Nov 18, 1888 – Feb 28, 1989) is considered to be the grandfather of modern Yoga. He was born on November 18th 1888 in the village of Muchukundapuram in the state of Karnataka India. Shri Krishnamacharya’s lineage can be traced to the Yogi Nathamuni who was a ninth century South Indian saint. Nathamuni is renowned for two great works in Sanskrit and Yoga, the Nyayatattva and the Yoga Rahasya. Krishnamacharya’s initial education was under his father who taught him the Vedas and the other religious texts. He lost this precious guidance at the age of ten when his father died.

The entire family then moved to Mysore to join his grandfather who was the head of the Parakala Math. It is here that he studied Sanskrit grammar, Vedanta and Tarka (logic) under the religious Guru to the Maharaja of Mysore. Over the subsequent years Krishnamacharya learned all six of the traditional schools of Hindu philosophy.

He became renowned for his ability to cite passages from all the texts at will and won great praise for his insight and knowledge.In his early adult years Krishnamacharya made a long pilgrimage through northern India, eventually finding his way to Tibet and the village of Mansarovar. There he met his Guru, Ramamohana Brahmachari and after prostrating and declaring his dedication was told he could stay. He was then introduced to his teacher’s wife and three children. Krishnamacharya lived with his teacher for seven and a half years learning Asana and Vinyasa practice, Yoga therapy, Pranayama and Yoga philosophy.

Upon leaving his Guru, Krishnamacharya was told two things “Get married and teach Yoga“. It was after practicing for over 25 years that he began to teach.Krishnamacharya was offered a position in Mysore by the Maharaja Krishna Rajendra Wodeyar to set up a Yoga program at the Jaganmohan palace. He accepted, apparently despite numerous offers elsewhere, mainly to be closer to his family of origin.

It was from this location that he taught many students including K.P Jois and B.K.S Iyengar. In 1925 he married Namagiriamma and through this union his family grew to include six children. Shortly after India obtained its independence the newly placed local government was forced to close the school down due to insufficient funding.

Krishnamacharya and his family then relocated to Madras in 1950.It is through Krishnamacharya’s teachings that the systems of Ashtanga Yoga (K.P. Jois), Iyengar Yoga (B.K.S. Iyengar) and Vini Yoga (T.K.V. Desikachar) were each developed. In the early years at the Jaganmohan palace Krishnamacharya taught the Vinyasa Krama method; the linking of postures together in sequence by numbers.

This has since been called “Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga” by Shri K.P. Jois. It has been said that Krishnamacharya’s understanding of the Vinyasa method was confirmed through his discovery of a copy of Rishi Vamana’s “Yoga Korunta” at Calcutta University. As there is no written documentation to verify this, the exact knowledge of the Yoga Korunta passed with Krishnamacharya.

Shri T. Krishnamacharya’s style of teaching Yoga changed over time. He used the Ashtanga Vinyasa method early on in his teaching years, though apparently he also always focused on the individual needs of the student. He believed that creating personal programs and teaching them on a one-on-one basis was the most beneficial and therapeutic way a student could practice Yoga. By taking into account the practitioners life (age, body type, family responsibilities and profession) a unique system of Yoga was developed for each student.

Creating an individual program allowed Krishnamacharya to apply his understanding of all his life’s research into a well rounded Yoga program that included Pranayama, Asana, meditation, chanting and the study of scriptures.Krishnamacharya’s legacy should also honour the love and devotion he had for his family. He was offered the position of Head Swami of the Parakala Math but he chose to decline. His reply to each of the three times that he was asked was that he wished to spend time with his family. Krishnamacharya passed away in 1989 at the age of one-hundred. His later teachings continue to be taught by his son and grandson in Madras, India.

Advaita Vedanta

So what is Advaita Vedànta? Literally it means non-dual teaching. What is it to be not-separate? When self inquiry is honest and direct, we can experience all objects that come across our screen of attention as “not I”.

You have a body, but you experience it. Not I. You have feelings, but you experience them. Not I. You have a mind, but you experience thoughts. Not I. Only the experiencer is perceiving. Can you perceive the perceiver? Can you find the one who is looking? If there is anything that is found, anything that comes and goes, it is not-self. Only that which is, the abiding self, undifferentiated consciousness, remains ever-present. It cannot be witnessed, and can only be witnessed from. So do not become that which you are not. Don’t put energy into false beliefs and attached identities. Even your personality, your sex, your culture, all of these things come and go. They are not you. Thus all beings are of merit, all beings deserve compassion and love.

One of the terms in traditional Dualistic Yoga that crosses over into Non-Dual Advaita practices is Kaivalya. It means to be alone (not lonely!) and to be non-attached. The solitude or emptiness described in non-dualism is similar to that described in dualistic practices, despite that they may disagree on how to get there.

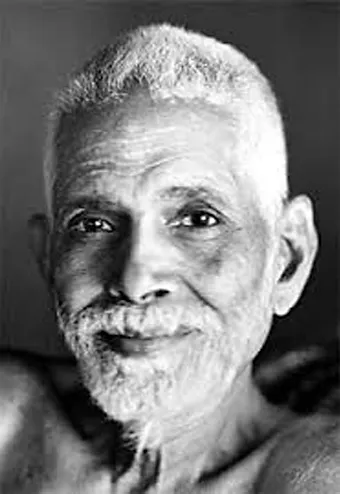

Bhagavan Ràmana Mahàrshi

My first introduction to Advaita Vedànta was in the early 1990s in India when I first started to read about Ràmana Mahàçùi. To this day I consider Ràmana as Bhagavan, the beloved, or the adored one.

Ràmana Mahàrshi (30 December 1879 – 14 April 1950), was born in what is now Tiruchuli, Tamil Nadu, India. In 1895, an attraction to the sacred hill Arunachala was aroused in him, and in 1896, at the age of 16, he had a “death-experience” where he became aware of a “current” or “force” which he recognised as his true “I” or “self”.

Ràmana Mahàrshi approved a number of paths and practices, but recommended self-inquiry as the principal means to remove ignorance and abide in Self-awareness, together with Bhakti (devotion) or surrender to the Self. Bhagavan Ràmana was known to answer questions based on the level of the questioner. If a seeker came with questions on the Guna, or a more personal question he would answer those questions, typically in a more theoretical way. If the question showed deeper spiritual yearning or application he answered on the deepest level possible, and the seeker was transformed.

Here are some of my favorite quotes from him:

“Wanting to reform the world without discovering one’s true self is like trying to cover the world with leather to avoid the pain of walking on stones and thorns. It is much simpler to wear shoes.”

“All that is required to realise the Self is to ‘Be Still.'”

“You can only stop the flow of thoughts by refusing to have any interest in it.”

“Become conscious of being conscious. Say or think “I am”, and add nothing to it. Be aware of the stillness that follows the “I am”. Sense your presence, the naked unveiled, unclothed beingness. It is untouched by young or old, rich or poor, good or bad, or any other attributes. It is the spacious womb of all creation, all form.”

Adi Shankaracharya

My own explorations have lead me further along the path of non-dualism, and currently Advaita is what I use most as a central reference point for my other daily Yoga “activities” and teachings. For me it has taken ongoing research and development to reconcile these different aspects.

Modern (neo) Advaita Vedanta does not typically allow or encourage technical practices in addition to the “non-dual” witnessing. As I am also a practitioner of Yoga, Vinyasa Krama, Pranayama and Gestalt Therapy, there may be some contradiction between Advaita and these “techniques”. Simply enough, each of these techniques I apply individually, moment by moment. I am not interested in further conditions and improvement: each one is addressing a different aspect of “I”, and can be picked up or dropped as needed. Nothing is necessary. Everything is good.

In modern Advaita Vedanta, there can be a tendency to reject all technique, all practices, that aren’t “nothing”. I find this both impractical, and just as attached as doing something. As other teachers have said – any method is fine, just be careful what you believe in.

Adi Shankara was an early 8th century Indian philosopher and theologian who consolidated the doctrine of Advaita Vedanta. He is credited with unifying and establishing the main currents of thought in Hinduism. His teaching of “nirguna” or Brahma without qualities, is a direct path linking simple Pranayama techniques with the Advaita concept of awareness – “consciousness is all there is.”

One compatible source for linking Hatha Yoga, Pranayama and Advaita is the Yoga Taravali – particularly the breathing and meditation practices mentioned therein. Taravali means a necklace of stars, or a lineage of stars: the teachings of Advaita from one Guru to the next. Below is a Sloka from the Yoga Taravali:

If one focuses gradually and carefully on the anàhata, And practices the stambha with courage, The mind and breath are naturally suspended;

Then there blooms the splendour of the kevala kumbhaka

Over the years I have developed an evolving and insightful Pranayama practice, sourcing both the Yoga Taravali, my own experiences with different teachers, some of the other Hatha traditions, and most importantly the need to teach Pranayama based on self-practice versus led classes.

Basically there are very few Yoga teachers that I know that are teaching both self practice classes, and a therapeutic system of Pranayama – taught individually vs collectively – that progresses directly to a deeper meditation.

The simplicity of witnessing one’s energy and observing the Stambha and then tracing the path back to the observer is a profound and delicate dance that is possible for any committed and patient practitioner.